« メディアの世論調査結果を検証する | 最新記事 | 反・脱・卒・減・縮・原発を修飾する言葉について »

2014年7月14日

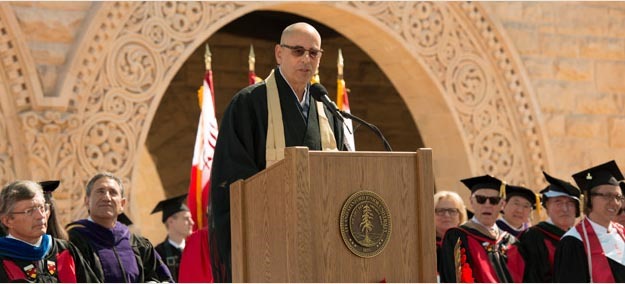

Zen Buddhist priest urges Stanford graduates to cultivate spiritual practices

今年2014年のスタンフォード大学卒業式において、曹洞宗の国際布教師 ノーマン・フィッシャー像穴師が訓示を行いました。

演題は “How to Survive Your Promising Life” です。

Zen Buddhist priest urges Stanford graduates to cultivate spiritual practices

Baccalaureate speaker Zoketsu Norman Fischer told graduates that their promising lives would be filled with challenges, but love and a regular spiritual practice that has no agenda would bolster them for the journey ahead.

Zen Buddhist priest urges Stanford graduates to cultivate spiritual practices

Baccalaureate speaker Zoketsu Norman Fischer told graduates that their promising lives would be filled with challenges, but love and a regular spiritual practice that has no agenda would bolster them for the journey ahead.

Addressing the Class of 2014, Zoketsu Norman Fischer, a Zen Buddhist priest and poet, urged Stanford graduates to cultivate regular spiritual practices to survive the difficult human journey of life with their "hearts intact" and their "love generous and bright."Fischer, who spoke Saturday morning in the Main Quad at Baccalaureate, a multifaith celebration for graduating students and their families and friends, titled his address, "How to Survive Your Promising Life." Fischer, the founder of the Everyday Zen Foundation, said the defining characteristic of a spiritual practice is that it must be "useless, absolutely useless.""You've been doing lots of good things for lots of good reasons for a long time now," he said, "for your physical health, your psychological health, your emotional health, for your family life, for your future success, for your economic life, for your community, for your world. But a spiritual practice is useless. It doesn't address any of those concerns. It's a practice that we do to touch our lives beyond all concerns – to reach beyond our lives to their source." Fischer, a former abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center, the oldest and largest Buddhist institution in the West, said his practice for many years has been simply to sit in silence. He said spiritual practices come from love, encourage love and produce more love. They require imagination and are unlimited in their variety. "Whether or not you believe in God, you could pray," he said. "You can contemplate spiritual texts or art, poetry, sacred music. You could just walk quietly on the Earth as a spiritual practice. You could gaze at the landscape or the sea or the sky. A little tip: If you're ever in trouble, look up at the sky for a few minutes and you'll feel better." Among the other spiritual practices Fischer offered was compassion – going toward, rather than turning away from, the suffering of others and your own suffering. "Can you become softened and brought to wisdom by the unavoidable pain of yourself or others?" he asked. Or you could practice gratitude, he said. He recommended that the first thing graduates do each morning is "train yourself to close your eyes, just be quiet for a moment, and say softly to yourself the word 'grateful,' and see what comes into your mind." Fisher urged the graduates to think seriously about creating spiritual practices, but not without a certain amount of joy and lightness."Today you are hurtling out of heaven," he said. "Where in the world will you land? When you get there, what in the world are you going to do? What is really worthwhile and what is just a distraction – no matter how much people tell you it's not? This is not a simple thing. You're going to have to figure these things out. Nobody but you can do that."The Baccalaureate celebration opened with a solemn Buddhist call to prayer performed on a singing bowl and ended with a dramatic drumming blessing, Tatsumaki (Whirlwind), performed by Stanford Taiko. In between there was an invocation, "A Prayer of the Ojibway Nation"; a benediction; and two readings: "I Have Learned So Much," by Hafiz of Shiraz, and a Zen-inspired translation of Psalm 124 by Fischer. Stanford Talisman, a student a cappella group, performed two songs, "Wanting Memories," a song of the African diaspora, and "One by One," a Xhosa song that was inspired by the South African anti-apartheid movement. (Stanford Report, June 14, 2014)

ノーマン・フィッシャー像穴師の訓示全文が公開されておりますので、ご紹介いたします。

Prepared text of Zoketsu Norman Fischer's Baccalaureate address

Following is the prepared text of "How to Survive Your Promising Life," the 2014 Baccalaureate address by Zoketsu Norman Fischer, Zen Buddhist priest, poet and founder of the Everyday Zen Foundation.

Good morning, everyone. I am honored to be here this morning with all of you. It is, literally, awesome to see ? a sea, an actual sea, of waving faces. I have no idea why I am here, but I feel quite lucky to have the chance to reflect, to muse, to ponder with you at this important moment in your lives. A moment is a moment. It is a long while since I have been a university student. I enjoyed that time in my life immensely. It was full and it was exiting, a time almost completely devoted to study and exploration of life's big questions, with a little fun thrown in, and powerful friendships, and, yes, a certain amount of misery and angst. College is a privilege, but it is not necessarily the easiest time of life. As with all other times of life ? but perhaps even moreso ? there are highs and there are lows. I hope today you are feeling the high. But time passes and you forget. These days when I go to university campuses, which I do from time to time, I feel as if I were in heaven. I imagine that heaven must be exactly like a university campus ? everyone young and healthy, spending their time in social and intellectual pursuits, flowers in season, the trees well trimmed, the lawns manicured, the buildings more or less matching and clean. A university is by definition a place of promise ? and students are promising individuals ? you perhaps more than most because Stanford is more than just another university, it is a great and storied university that, these days, seems to be at the center of the universe. Because of what you have received ? not only from Stanford, but also from your families and friends, who have given you a lot of love and support ? you now have the skills and the connections ? and the obligation ? to do great things. And this means not only great things for yourselves: You are expected to do great things for others, and for the world. We all have high hopes for you, probably higher hopes than you have for yourselves. Let's be honest ? as much as we discuss and practice wise punditry, we older people don't really know what the world will require in the coming times ? and we are a bit bewildered, and unsure, though we hate to admit it. To grow old is to gradually cease to understand the times in which you live. So we are placing our trust and our hope in you. No pressure, of course. But the promise of the future really is yours. And yet the truth is, it is not going to be so easy to survive your promising life. For one thing, there are a lot of promising young people out there ? not only here at Stanford, or here in California, here in the United States, but also in Europe, in China, in Latin America, all over Asia, and in India, and Africa ? some of you in fact are those people ? bright, energetic, and mobile. With so much competition, and so much anxiety about that competition, it is possible that success, if it comes, will not come easily. It is also of course possible that success will not come ? or that it will come, abundantly, but that you will not find it as meaningful as you had expected. It is also possible that success comes, and you do find it meaningful and satisfying ? but only at first, when it is still bright and shiny. And that later, the state and pace and social implications of the successful and ambitious life you will have lived will wear you down, and you'll find yourself tired and bewildered. It's also possible that as time stretches on your personal relationships will not work out as you had hoped, your sense of yourself will not hold up to scrutiny, that there will be disappointments and setbacks, acknowledged and unacknowledged ? in short, it is possible, even likely, that there is some pain awaiting you as you go forth from this bright day ? ruptured love affairs, betrayals, losses, disillusionments ? seriously shaky moments. It's possible too that, as you move through the decades, it will become increasingly difficult for you to maintain the idealism and the hopefulness you have today. It's possible that one day you will find yourself wondering what you have been doing all these years, and who you have become. It's possible the life you wanted and have built will not be as you'd expected it to be. It's possible that the world you wanted and hoped to improve will not improve. Anyway, you will keep busy, you will have things to do. And you will try not to notice such feelings. You will try to deny any despair or disappointment or discouragement or boredom you may be feeling two, five, ten, fifteen, or twenty years from today. And probably you will be able ? more or less ? to do that. But only more or less. I am sorry to say all these things to you on such a wonderful day and in such a beautiful place as this. I realize that baccalaureate speeches are supposed to be bright, uplifting, and encouraging. The folks at Stanford who invited me to speak today sent me links to previous baccalaureate talks so I would know how they usually go. The speeches I looked at were wonderful ? they were serious about challenges ahead ? but they were always positive. So, yes, I too intend to say something bright and encouraging. But I thought I would be more convincing if I were also realistic. And it is realistic to say that your lives from now on are likely not going to be entirely smooth sailing. The skills you'll need to survive may be more than or other than the skills you have been focusing on so far in your life. The truth is, it takes a great deal of fortitude and moral strength to sustain a worthwhile, happy, and virtuous human life over time in the world as it actually is. OK, here is the uplifting part: Your life isn't and has never been about you. It isn't and has never been about what you accomplish, how successful you are or are not, how much money you make, what sort of position you ascend to, or even about your family, your associations, your various communities, or how much good you do for others or the world at large. Your life, like mine, and like everyone else's, has always been about one thing: love. Who are you, really? Where did you come from? Why were you born? When this short human journey is over, where are you going? Why ? and how ? does any of this exist? What is the purpose and the point of it all? Not even your Nobel Prize-winning professors know the answers to these questions, the inevitable, unavoidable, human questions. None of us knows the answers. All we know is that we are here for a while before we are gone, and that we are here together. The only thing that makes sense and that is completely real is love. Love is the only answer. This is no mystery ? everyone knows this. Whether your destiny is to have a large loving family or to have no partner and no family ? love is available to you wherever you look. And when you dedicate yourself to love, to trying your best to be kind and to benefit everyone you meet ? not just the people on your side, not just the people you like and approve of, but everyone, every human and nonhuman being ? then you will be OK and your life ? whatever it brings, even if it brings a lot of difficulty and tragedy ? as so many lives do ? as even the lives of very privileged and promising people sometimes do ? your life will be a beautiful life. As I promised, this is uplifting ? or at least I hope you find it uplifting. But there's more. How do you love? How do you make love real in your life? This doesn't happen by itself. It takes attention, it takes commitment, continuity, effort. It won't come automatically, it won't come from wishing or from believing or assuming. You are going to have to figure out how to not get distracted by your personal problems, by your success or your lack of success, by your needs, your desires, your suffering, your various interests, and keep your eye on the ball of love even as, inevitably, you juggle all the rest of it. To find and develop love you have to firmly commit yourself to love. And you have to have a way, a path, a practice, for cultivating love throughout your lifetime, come what may. Love isn't a just feeling. It is an overarching attitude and spirit. It's a way of life. It's a daily activity. In my life I have cultivated love through a path of spiritual practice, a life of meditation and study and reflection. I think you also will need a path of spiritual practice. You also will need some kind of religious life if you are going to survive this difficult human journey with your heart intact and your love generous and bright. A spiritual or a religious life doesn't need to look like what we have so far thought of as a spiritual life. The world now is too various and connected for the old paths to work. Not that the old paths are outmoded ? they are as useful today as they ever were, perhaps moreso. But they need to be re-formatted, re-configured, for our lives as they are now. And above all, they need to be open and tolerant, transparent and porous rather than opaque, and expansive rather than exclusive. A spiritual life can and should be much more lively and various and interesting than we have previously imagined. To investigate at the deepest possible level the human heart and the purposes of a human life that is essentially connected at all points to and with others and the planet Earth can be ? and should be, maybe must be ? deeply engaging and satisfying. There are a million ways to approach it. But the main thing is, I think, that you need some commitment, some discipline ? and you need a regular practice, something you actually do. The most important characteristic ? the defining characteristic, I would say ? of a spiritual practice is that it is useless. That is, it is an activity that has no other practical purpose than to connect you to your heart and to your highest and most mysterious purpose ? a purpose that is literally unknown, because it references the unanswerable questions I mentioned a moment ago. We do so many things for so many good reasons ? for our physical or psychological or emotional health, for our family life or economic life, for the world. But a spiritual practice is useless ? it doesn't address any of those concerns. It is a practice that we do to touch our lives beyond all concerns ? reaching beyond our lives to their source. For me that practice is and has been for a long time sitting in silence. That's a good one; maybe it will also be good for you. I certainly recommend it to everyone ? regardless of your religious affiliation or lack of one. But there are many others. Prayer, for one. Whether or not you believe in God you can pray. You can contemplate spiritual texts or art, poetry, or sacred music. You can walk quietly on the Earth. You can gaze at the landscape or the sea or sky. And there are many other such useless practices you can devise or invent. You could practice gratitude ? when you wake up every morning, as soon as you put your feet on the floor from bed, sitting on the side of the bed you can close your eyes, be quiet for a minute, and say the word "grateful" to yourself silently, and just sit there for a moment or two and see what happens. You could practice that right now… Or you could practice giving ? always making the effort to intentionally say a word or offer a smile or material or emotional gifts that confer blessings on another person. Or you could practice kind speech ? on all occasions, even difficult ones, committing yourself to speaking as much as you can in kindness and with inclusion of others and their needs, their hopes and dreams. Not just speaking from your own side. Or you could practice beneficial action, committing yourself to intentionally acting with a spirit of benefiting others, of being of some use to others, in whatever way you can, even stupid ways that seem not to be useful or beneficial but could be if you intend them to be. For instance, you can practice benefiting others by wiping sink counters in public restrooms, or in your own kitchen. Wiping counters with a spirit of beneficial action ? with that thought in your mind intentionally ? can be a daily spiritual discipline. Or you can cook a meal with love for others, with a spirit of benefiting others. Even if the meal is for yourself, you can benefit yourself with the good food, that you paid close attention to when you prepared it, because one's self, truly and kindly understood, is also another. Or you could practice identity action ? recognizing that when you do anything, whatever it is, you are not, and cannot, do it alone, by your own power. Inevitably whatever you do involves others and the whole world, this Earth we live on, its life-giving sunlight and plants and animals. So that every action we ever take involves others and a world of support. You could notice that whenever you do anything. Or you could practice compassion ? going toward, rather than turning away from, the suffering of others ? and your own suffering too. We all want to avoid pain, to make it disappear. But when it's impossible to make the pain disappear you can go toward it rather than running away ? you can become softened by it. I could go on and on. Spiritual practices are unlimited ? and they are imaginative. And ? especially ? full of love. They come from love, they encourage love, and they produce love. When you do them over time you find that you are living in a world full of love. And for your life and for our lives collectively in the times to come we are going to need love ? lots of love. In good times, love is lovely. Nothing can be better. And in hard times, love is necessary. It turns tragedy into opportunity ? something difficult and unwanted becomes a chance to drive love deeper, to make it wiser, fuller, more glorious, and more resilient. A while ago my friend Fenton Johnson, who is a wonderful novelist and writer and professor of literature, and a lifelong spiritual practitioner ? and who is sitting in the audience today! ? sent me an email about this talk. He wrote, "If I were giving such an address I'd talk about the mystery of life, how one can and should lay great plans, but how life has its own ebb and flow, and our first duty is to be present to that ebb and flow, to realize that failure and success are social conceptions that can be useful but that in their conventional definitions have little to do with what really matters, which is the study and practice of virtue." As Timothy Kelly, who was abbot of Gethsemani Monastery, Thomas Merton's monastery in Kentucky, said, "How one lives one's life is the only true measure of the validity of one's search." The Beat poet Philip Whalen was my dear friend and teacher. Like me, he was also a Zen Buddhist priest. As a poet and a spiritual practitioner, he couldn't do anything other than search. His genius was that he could express the seriousness of his search while maintaining not only his sense of humor and play ? but also a clear and sane knowledge that the whole thing is actually as ridiculous as it is tragic. Here is a poem of his, written in the 1960s: TO HENRIK IBSEN This world is not The world I want Is Heaven & I see There's more of them * I've seen most of this world is ocean I know if I had all I wanted from it There'd still not be enough Someone would be lonely hungry toothache All this world with a red ribbon on it Not enough Nor several hells heavens planets Universal non-skid perfection systems Where's my eternity papers? Get me the great Boyg on the phone. Connect me with the Button Moulder right away. So please do seriously think about it ? but not without some joy and some lightness. Today you are closing the door on one life and opening the door to another. Today you fall out of heaven. Where will you land? What will you do there? What is really worthwhile and what is just distraction ? however much people tell you it is not? You are the only one who can ask and answer these questions. So I am saluting you this morning ? you and the wonderful life of promise you have lived up to this moment, and the new life of challenge and difficulty and passion that you are entering. Cheers and congratulations. (Stanford Report)

ヘンリック・イプセンの詩を引用しての訓示でした。

ノーマン・フィッシャー像穴師は、鈴木俊隆師により1962年に設立された﹁サンフランシスコ禅センター﹂の曹洞宗国際布教師です。

スタンフォード大学卒業式での訓示といえば、禅の影響を受けたとされるスティーブ・ジョブズの訓示を想起します。

スティーブ・ジョブズの卒業式訓示はこちらにまとめておりますので併せて御覧ください。

⇒スティーブ・ジョブズの卒業式訓示︵SOTO禅インターナショナルシンポジウム資料︶ (PDF)

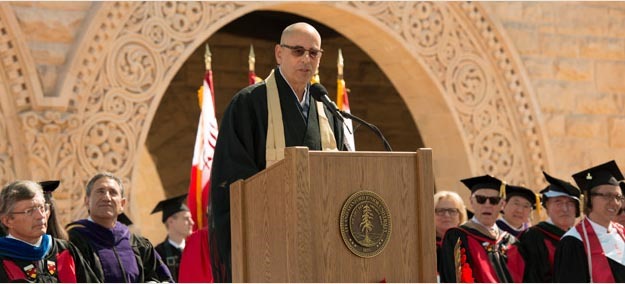

Zen Buddhist priest urges Stanford graduates to cultivate spiritual practices

Baccalaureate speaker Zoketsu Norman Fischer told graduates that their promising lives would be filled with challenges, but love and a regular spiritual practice that has no agenda would bolster them for the journey ahead.

Zen Buddhist priest urges Stanford graduates to cultivate spiritual practices

Baccalaureate speaker Zoketsu Norman Fischer told graduates that their promising lives would be filled with challenges, but love and a regular spiritual practice that has no agenda would bolster them for the journey ahead.

Addressing the Class of 2014, Zoketsu Norman Fischer, a Zen Buddhist priest and poet, urged Stanford graduates to cultivate regular spiritual practices to survive the difficult human journey of life with their "hearts intact" and their "love generous and bright."Fischer, who spoke Saturday morning in the Main Quad at Baccalaureate, a multifaith celebration for graduating students and their families and friends, titled his address, "How to Survive Your Promising Life." Fischer, the founder of the Everyday Zen Foundation, said the defining characteristic of a spiritual practice is that it must be "useless, absolutely useless.""You've been doing lots of good things for lots of good reasons for a long time now," he said, "for your physical health, your psychological health, your emotional health, for your family life, for your future success, for your economic life, for your community, for your world. But a spiritual practice is useless. It doesn't address any of those concerns. It's a practice that we do to touch our lives beyond all concerns – to reach beyond our lives to their source." Fischer, a former abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center, the oldest and largest Buddhist institution in the West, said his practice for many years has been simply to sit in silence. He said spiritual practices come from love, encourage love and produce more love. They require imagination and are unlimited in their variety. "Whether or not you believe in God, you could pray," he said. "You can contemplate spiritual texts or art, poetry, sacred music. You could just walk quietly on the Earth as a spiritual practice. You could gaze at the landscape or the sea or the sky. A little tip: If you're ever in trouble, look up at the sky for a few minutes and you'll feel better." Among the other spiritual practices Fischer offered was compassion – going toward, rather than turning away from, the suffering of others and your own suffering. "Can you become softened and brought to wisdom by the unavoidable pain of yourself or others?" he asked. Or you could practice gratitude, he said. He recommended that the first thing graduates do each morning is "train yourself to close your eyes, just be quiet for a moment, and say softly to yourself the word 'grateful,' and see what comes into your mind." Fisher urged the graduates to think seriously about creating spiritual practices, but not without a certain amount of joy and lightness."Today you are hurtling out of heaven," he said. "Where in the world will you land? When you get there, what in the world are you going to do? What is really worthwhile and what is just a distraction – no matter how much people tell you it's not? This is not a simple thing. You're going to have to figure these things out. Nobody but you can do that."The Baccalaureate celebration opened with a solemn Buddhist call to prayer performed on a singing bowl and ended with a dramatic drumming blessing, Tatsumaki (Whirlwind), performed by Stanford Taiko. In between there was an invocation, "A Prayer of the Ojibway Nation"; a benediction; and two readings: "I Have Learned So Much," by Hafiz of Shiraz, and a Zen-inspired translation of Psalm 124 by Fischer. Stanford Talisman, a student a cappella group, performed two songs, "Wanting Memories," a song of the African diaspora, and "One by One," a Xhosa song that was inspired by the South African anti-apartheid movement. (Stanford Report, June 14, 2014)

ノーマン・フィッシャー像穴師の訓示全文が公開されておりますので、ご紹介いたします。

Good morning, everyone. I am honored to be here this morning with all of you. It is, literally, awesome to see ? a sea, an actual sea, of waving faces. I have no idea why I am here, but I feel quite lucky to have the chance to reflect, to muse, to ponder with you at this important moment in your lives. A moment is a moment. It is a long while since I have been a university student. I enjoyed that time in my life immensely. It was full and it was exiting, a time almost completely devoted to study and exploration of life's big questions, with a little fun thrown in, and powerful friendships, and, yes, a certain amount of misery and angst. College is a privilege, but it is not necessarily the easiest time of life. As with all other times of life ? but perhaps even moreso ? there are highs and there are lows. I hope today you are feeling the high. But time passes and you forget. These days when I go to university campuses, which I do from time to time, I feel as if I were in heaven. I imagine that heaven must be exactly like a university campus ? everyone young and healthy, spending their time in social and intellectual pursuits, flowers in season, the trees well trimmed, the lawns manicured, the buildings more or less matching and clean. A university is by definition a place of promise ? and students are promising individuals ? you perhaps more than most because Stanford is more than just another university, it is a great and storied university that, these days, seems to be at the center of the universe. Because of what you have received ? not only from Stanford, but also from your families and friends, who have given you a lot of love and support ? you now have the skills and the connections ? and the obligation ? to do great things. And this means not only great things for yourselves: You are expected to do great things for others, and for the world. We all have high hopes for you, probably higher hopes than you have for yourselves. Let's be honest ? as much as we discuss and practice wise punditry, we older people don't really know what the world will require in the coming times ? and we are a bit bewildered, and unsure, though we hate to admit it. To grow old is to gradually cease to understand the times in which you live. So we are placing our trust and our hope in you. No pressure, of course. But the promise of the future really is yours. And yet the truth is, it is not going to be so easy to survive your promising life. For one thing, there are a lot of promising young people out there ? not only here at Stanford, or here in California, here in the United States, but also in Europe, in China, in Latin America, all over Asia, and in India, and Africa ? some of you in fact are those people ? bright, energetic, and mobile. With so much competition, and so much anxiety about that competition, it is possible that success, if it comes, will not come easily. It is also of course possible that success will not come ? or that it will come, abundantly, but that you will not find it as meaningful as you had expected. It is also possible that success comes, and you do find it meaningful and satisfying ? but only at first, when it is still bright and shiny. And that later, the state and pace and social implications of the successful and ambitious life you will have lived will wear you down, and you'll find yourself tired and bewildered. It's also possible that as time stretches on your personal relationships will not work out as you had hoped, your sense of yourself will not hold up to scrutiny, that there will be disappointments and setbacks, acknowledged and unacknowledged ? in short, it is possible, even likely, that there is some pain awaiting you as you go forth from this bright day ? ruptured love affairs, betrayals, losses, disillusionments ? seriously shaky moments. It's possible too that, as you move through the decades, it will become increasingly difficult for you to maintain the idealism and the hopefulness you have today. It's possible that one day you will find yourself wondering what you have been doing all these years, and who you have become. It's possible the life you wanted and have built will not be as you'd expected it to be. It's possible that the world you wanted and hoped to improve will not improve. Anyway, you will keep busy, you will have things to do. And you will try not to notice such feelings. You will try to deny any despair or disappointment or discouragement or boredom you may be feeling two, five, ten, fifteen, or twenty years from today. And probably you will be able ? more or less ? to do that. But only more or less. I am sorry to say all these things to you on such a wonderful day and in such a beautiful place as this. I realize that baccalaureate speeches are supposed to be bright, uplifting, and encouraging. The folks at Stanford who invited me to speak today sent me links to previous baccalaureate talks so I would know how they usually go. The speeches I looked at were wonderful ? they were serious about challenges ahead ? but they were always positive. So, yes, I too intend to say something bright and encouraging. But I thought I would be more convincing if I were also realistic. And it is realistic to say that your lives from now on are likely not going to be entirely smooth sailing. The skills you'll need to survive may be more than or other than the skills you have been focusing on so far in your life. The truth is, it takes a great deal of fortitude and moral strength to sustain a worthwhile, happy, and virtuous human life over time in the world as it actually is. OK, here is the uplifting part: Your life isn't and has never been about you. It isn't and has never been about what you accomplish, how successful you are or are not, how much money you make, what sort of position you ascend to, or even about your family, your associations, your various communities, or how much good you do for others or the world at large. Your life, like mine, and like everyone else's, has always been about one thing: love. Who are you, really? Where did you come from? Why were you born? When this short human journey is over, where are you going? Why ? and how ? does any of this exist? What is the purpose and the point of it all? Not even your Nobel Prize-winning professors know the answers to these questions, the inevitable, unavoidable, human questions. None of us knows the answers. All we know is that we are here for a while before we are gone, and that we are here together. The only thing that makes sense and that is completely real is love. Love is the only answer. This is no mystery ? everyone knows this. Whether your destiny is to have a large loving family or to have no partner and no family ? love is available to you wherever you look. And when you dedicate yourself to love, to trying your best to be kind and to benefit everyone you meet ? not just the people on your side, not just the people you like and approve of, but everyone, every human and nonhuman being ? then you will be OK and your life ? whatever it brings, even if it brings a lot of difficulty and tragedy ? as so many lives do ? as even the lives of very privileged and promising people sometimes do ? your life will be a beautiful life. As I promised, this is uplifting ? or at least I hope you find it uplifting. But there's more. How do you love? How do you make love real in your life? This doesn't happen by itself. It takes attention, it takes commitment, continuity, effort. It won't come automatically, it won't come from wishing or from believing or assuming. You are going to have to figure out how to not get distracted by your personal problems, by your success or your lack of success, by your needs, your desires, your suffering, your various interests, and keep your eye on the ball of love even as, inevitably, you juggle all the rest of it. To find and develop love you have to firmly commit yourself to love. And you have to have a way, a path, a practice, for cultivating love throughout your lifetime, come what may. Love isn't a just feeling. It is an overarching attitude and spirit. It's a way of life. It's a daily activity. In my life I have cultivated love through a path of spiritual practice, a life of meditation and study and reflection. I think you also will need a path of spiritual practice. You also will need some kind of religious life if you are going to survive this difficult human journey with your heart intact and your love generous and bright. A spiritual or a religious life doesn't need to look like what we have so far thought of as a spiritual life. The world now is too various and connected for the old paths to work. Not that the old paths are outmoded ? they are as useful today as they ever were, perhaps moreso. But they need to be re-formatted, re-configured, for our lives as they are now. And above all, they need to be open and tolerant, transparent and porous rather than opaque, and expansive rather than exclusive. A spiritual life can and should be much more lively and various and interesting than we have previously imagined. To investigate at the deepest possible level the human heart and the purposes of a human life that is essentially connected at all points to and with others and the planet Earth can be ? and should be, maybe must be ? deeply engaging and satisfying. There are a million ways to approach it. But the main thing is, I think, that you need some commitment, some discipline ? and you need a regular practice, something you actually do. The most important characteristic ? the defining characteristic, I would say ? of a spiritual practice is that it is useless. That is, it is an activity that has no other practical purpose than to connect you to your heart and to your highest and most mysterious purpose ? a purpose that is literally unknown, because it references the unanswerable questions I mentioned a moment ago. We do so many things for so many good reasons ? for our physical or psychological or emotional health, for our family life or economic life, for the world. But a spiritual practice is useless ? it doesn't address any of those concerns. It is a practice that we do to touch our lives beyond all concerns ? reaching beyond our lives to their source. For me that practice is and has been for a long time sitting in silence. That's a good one; maybe it will also be good for you. I certainly recommend it to everyone ? regardless of your religious affiliation or lack of one. But there are many others. Prayer, for one. Whether or not you believe in God you can pray. You can contemplate spiritual texts or art, poetry, or sacred music. You can walk quietly on the Earth. You can gaze at the landscape or the sea or sky. And there are many other such useless practices you can devise or invent. You could practice gratitude ? when you wake up every morning, as soon as you put your feet on the floor from bed, sitting on the side of the bed you can close your eyes, be quiet for a minute, and say the word "grateful" to yourself silently, and just sit there for a moment or two and see what happens. You could practice that right now… Or you could practice giving ? always making the effort to intentionally say a word or offer a smile or material or emotional gifts that confer blessings on another person. Or you could practice kind speech ? on all occasions, even difficult ones, committing yourself to speaking as much as you can in kindness and with inclusion of others and their needs, their hopes and dreams. Not just speaking from your own side. Or you could practice beneficial action, committing yourself to intentionally acting with a spirit of benefiting others, of being of some use to others, in whatever way you can, even stupid ways that seem not to be useful or beneficial but could be if you intend them to be. For instance, you can practice benefiting others by wiping sink counters in public restrooms, or in your own kitchen. Wiping counters with a spirit of beneficial action ? with that thought in your mind intentionally ? can be a daily spiritual discipline. Or you can cook a meal with love for others, with a spirit of benefiting others. Even if the meal is for yourself, you can benefit yourself with the good food, that you paid close attention to when you prepared it, because one's self, truly and kindly understood, is also another. Or you could practice identity action ? recognizing that when you do anything, whatever it is, you are not, and cannot, do it alone, by your own power. Inevitably whatever you do involves others and the whole world, this Earth we live on, its life-giving sunlight and plants and animals. So that every action we ever take involves others and a world of support. You could notice that whenever you do anything. Or you could practice compassion ? going toward, rather than turning away from, the suffering of others ? and your own suffering too. We all want to avoid pain, to make it disappear. But when it's impossible to make the pain disappear you can go toward it rather than running away ? you can become softened by it. I could go on and on. Spiritual practices are unlimited ? and they are imaginative. And ? especially ? full of love. They come from love, they encourage love, and they produce love. When you do them over time you find that you are living in a world full of love. And for your life and for our lives collectively in the times to come we are going to need love ? lots of love. In good times, love is lovely. Nothing can be better. And in hard times, love is necessary. It turns tragedy into opportunity ? something difficult and unwanted becomes a chance to drive love deeper, to make it wiser, fuller, more glorious, and more resilient. A while ago my friend Fenton Johnson, who is a wonderful novelist and writer and professor of literature, and a lifelong spiritual practitioner ? and who is sitting in the audience today! ? sent me an email about this talk. He wrote, "If I were giving such an address I'd talk about the mystery of life, how one can and should lay great plans, but how life has its own ebb and flow, and our first duty is to be present to that ebb and flow, to realize that failure and success are social conceptions that can be useful but that in their conventional definitions have little to do with what really matters, which is the study and practice of virtue." As Timothy Kelly, who was abbot of Gethsemani Monastery, Thomas Merton's monastery in Kentucky, said, "How one lives one's life is the only true measure of the validity of one's search." The Beat poet Philip Whalen was my dear friend and teacher. Like me, he was also a Zen Buddhist priest. As a poet and a spiritual practitioner, he couldn't do anything other than search. His genius was that he could express the seriousness of his search while maintaining not only his sense of humor and play ? but also a clear and sane knowledge that the whole thing is actually as ridiculous as it is tragic. Here is a poem of his, written in the 1960s: TO HENRIK IBSEN This world is not The world I want Is Heaven & I see There's more of them * I've seen most of this world is ocean I know if I had all I wanted from it There'd still not be enough Someone would be lonely hungry toothache All this world with a red ribbon on it Not enough Nor several hells heavens planets Universal non-skid perfection systems Where's my eternity papers? Get me the great Boyg on the phone. Connect me with the Button Moulder right away. So please do seriously think about it ? but not without some joy and some lightness. Today you are closing the door on one life and opening the door to another. Today you fall out of heaven. Where will you land? What will you do there? What is really worthwhile and what is just distraction ? however much people tell you it is not? You are the only one who can ask and answer these questions. So I am saluting you this morning ? you and the wonderful life of promise you have lived up to this moment, and the new life of challenge and difficulty and passion that you are entering. Cheers and congratulations. (Stanford Report)

投稿者: kameno 日時: 2014年7月14日 10:13